As my wife, our daughter, and my wife's mother Elaine drove from Evergreen to hike to Lake Isabelle last Friday, I learned that the lake (and the glacier remnant that feeds it) was named by Boulder County engineer Fred A. Fair, to honor his wife. However, though I crouched in the backseat of the car and searched on Google until the curvy roads made me sick, I could find nothing else. No record of Isabelle Fair. No indication of where she was from, who she was, or when she died. I found quite a bit of information about Fred, who had discovered both the Isabelle Glacier and the Fair Glacier in 1908, but none of the sites that detailed his biography mentioned anything about Isabelle. "It looks like Fred married two other women after Isabelle," I called to the front seat.

|

| A Wikipedia Commons photo, taken by Junius Henderson in 1910, of Isabelle Glacier |

My mother-in-law nodded. "She probably died in childbirth. Women so often did."

And so, as we set out from the Brainard Lake Trailhead, I started to brainstorm a blog post about women's fragile lives, about medical advances, maybe about child-bearing. I gazed at Lake Isabelle and wondered if Fred had lingered on its shore and mourned his wife Isabelle. I know about grief. I would add some of those thoughts to my blog post.

|

| Meredith and Mitike on the Jean Lunning Trail, on the way up to Lake Isabelle |

Finally Meredith, who had been watching my frustrated search from the other side of our bed, suggested I try Ancestry.com. Lately, I've been interested in building my family tree (and Meredith's) on that website, but I hadn't yet thought of it as a research tool for other purposes. I kissed her and then created a new tree entitled "Isabelle Fair," and began.

Ancestry.com is a little bit magical. It pulls from birth records, census records, military records, marriage records, and death records to help people build their family trees. I merely pretended I was Isabelle, added my spouse Fred A. Fair, and waited for the Ancestry.com green leaf, which indicates "hints" about connections to that person. And the mystery of Isabelle began to unfurl.

The first document Ancestry.com found was a U.S. Census record from Boulder in 1920. In that year, ten years after University of Colorado Museum of Natural History professor Junius Henderson named Isabelle Glacier and Fair Glacier in Fred Fair's honor, Fred lived with his wife "Isabell" and two roomers, a Leo and Helen Golden. No children.

Because I loved the romantic vision of Fred mourning on the edge of Lake Isabelle, I thought maybe Isabelle had died just after that. I found birth records for Fred Adam Fair (1926), John Henry Fair (1927) and Marion Jay Fair (1930), and noted that all three were the children of Fred and a woman named Mary Jane Burger, who died in 1932. I found a 1932 marriage record to Ruby Goodwin.

And then I found a death record of a Leo Francis Golden, who was born on April 27, 1921. I assumed his parents were Helen and Leo Golden, the roomers who lived with the Fairs -- until I learned (more Census records) that Helen was Leo's sister.

Finally, a 1930 Census record solved the mystery. In 1930, 8-year-old Leo lived with his parents in Los Angeles, California. His parents were Leo Elbert Golden, age 46, and Isabel Golden, age 46.

Sometime between the 1920 Census and the 1930 Census, Isabel (Isabelle? Isabell?) had divorced Fred, given birth to Leo F., married Leo E., and moved to California (it's not clear what order she did all of that, as I can't find her marriage record to Leo or her divorce record from Fred).

She did not die. In fact, she lived a long life in California, maybe happily, until the age of 83. Her son Leo Francis lived until the age of 92, dying in Sitka, Alaska, in 2014 (interestingly, I worked in Sitka in 2001 and visited often after that, and may have crossed paths at some point with Leo).

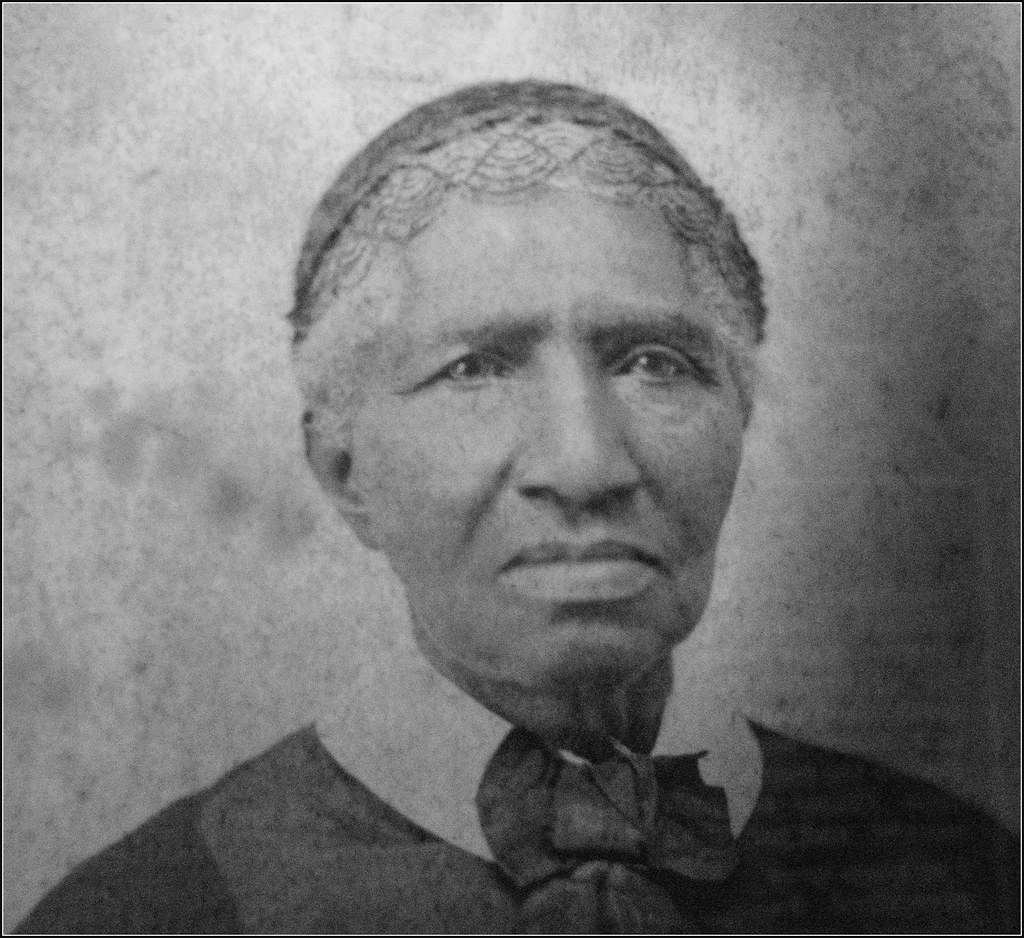

|

| The family tree Ancestry.com built for Isabel (Frances Isabel Womack) |

Fred may have brooded on the edge of Lake Isabelle, but out of anger or despair at his wife's departure, not at her death. Did they have children together? I can't find any evidence that they did, though they were married 18 years. That might explain Isabel's attraction to the new engineer, Leo.

What I do know: Professor Junius Henderson did not know how to spell "Isabel" when he marked the name on a lake and a glacier.

What I also know: I want to be a woman who lives my life as fully as I can, like I think Isabel did.

|

| Four women working to live their lives as bravely and boldly as possible. |

How to hike to Lake Isabelle and Isabelle Glacier:

1. Drive to the Brainard Lake Recreation Area, which requires a National Parks pass or the $11 day-use fee to enter. Note: even on a week-day in the summer, visitors who arrive later than 9 am will need to park in the day-use lot at Brainard Lake instead of at the Long Lake or Niwot Trailheads, which adds an extra mile round-trip to the hike.

2. Hike either the Niwot Cut-off Trail from the Niwot parking area or the Long Lake Trail from the Long Lake Trailhead. At the southern edge of Long Lake, you have a choice to hike the trail on the east shore or the Jean Lunning trail on the west shore -- in July, the flowers and the views on the Jean Lunning trail are magnificent.

3. At the end of Long Lake, take the Pawnee Pass Trail to Lake Isabelle. The trail zigzags steeply up to a shelf just before the lake, but the climb is well-worthwhile. People who want the expansive views hike all the way up to Pawnee Pass.

4. From the lake, the trail continues up to the remnant of Isabelle Glacier.

|

| The trail along Lake Isabelle toward the glacier. |

Sources:

Cockerell, T.D.A. "Junius Henderson." The Nautilus. 51 (3): 97-99. Retrieved from https://archive.org/stream/nautilus51amer#page/96/mode/2up. Web. 24 July 2017.

"Fair Family." Rootsweb.ancestry.com. 22 January 2016. Retrieved from http://wc.rootsweb.ancestry.com/cgi-bin/igm.cgi?op=GET&db=press&id=I613. 24 July 2017. Web.

"Glaciers of Colorado." Portland State University, 2009. Retrieved from http://glaciers.research.pdx.edu/Glaciers-Colorado. 24 July 2017. Web.

"Isabel Frances Womack Golden." Findagrave.com. Retrieved from https://www.findagrave.com/cgi-bin/fg.cgi/page/gr/%3Cbr%3E..http://www.findagrave.com/cgi-bin/fg.cgi?page=gr&GRid=177467606. 24 July 2017. Web.

"Leo F. Golden." www.tributes.com. Retrieved from http://www.tributes.com/obituary/show/Leo-F.-Golden-99393224. 24 July 2017. Web.

"Womack, Frances Isabel." Ancestry.com. 22 July 2017. Web.

|

| Bluebells and Lake Isabelle (July 2017) |

.jpg/220px-Rosalie_Osborne_Bierstadt%2C_seated%2C_unknown_date%2C_William_Kurtz_(restored).jpg)