Visit https://mountbluesky.info/ to see where this name change journey has gone! S__ Mountain is now officially named Mount Mestaa’ėhehe (the spelling was requested by the Arapaho and Cheyenne tribes). It IS possible to change these names!!! -- Sarah

Remember More Than Their Names: Colorado's Women and the Wild Places Named for Them

A blog about my quest to hike to all the Colorado summits and lakes named for women, to find out who those women were, and to write a book (trail guide meets history) about it.

Search This Blog

Click to Learn About the Women

- Aunt Clara Brown Hill (Central City)

- Belle and Helen Peak

- Emmaline Lake (Pinigree Park)

- Hessie Trail

- Lady Moon/Molly Lake (Red Feather Lakes)

- Lake Agnes (Cameron Pass)

- Lake Dorothy (Eldora)

- Lake Ethel (Berthoud Pass)

- Lake Isabelle (Ward)

- Mount Chiquita (RMNP)

- Mount Dickinson (RMNP)

- Mount Eva (Berthoud Pass)

- Mount Flora (Berthoud Pass)

- Mount Helen (Breckenridge)

- Mount Ida (RMNP)

- Mount Lady Washington (RMNP)

- Mount Margaret (Red Feather Lakes)

- Mount Rosalie (Bailey)

- Mount Silverheels (Breckenridge)

- Squaw Mountain (Idaho Springs)

Mount Chiquita (RMNP)

Mount Chiquita, 13,075 feet (MODERATE)

named for the fictional Ute woman Chiquita, from a 1902 novel

|

| Mount Chiquita from Fall River Pass (Photo by my dad, Richard H. Hahn -- visit his gallery, Alpenglow, in Estes Park) |

Getting to the trailhead: Follow Fall River Road from the Fall River entrance of the national park. Turn right at the turnoff for Old Fall River Road. Remember this is a one-way gravel road, and -- while almost any car can handle the drive, not every driver can handle the view of drop-offs! Drive up the Old Fall River Road 7.8 miles to the Chapin Pass trailhead. The park is crowded all summer; go very early if you want a parking space. When you go home, you’ll need to drive up and over onto Trail Ridge Road. Stop at the Alpine Visitor Center to admire the views first.

Roundtrip distance to the summit from trailhead: 5 miles RT

Elevation gain: 2,057 feet

Map: (to be included)

|

| The stars above (L to R) Chapin, Chiquita, and Ypsilon (photo by my dad, Richard H. Hahn) |

How to reach the summit:

1. The trail is well-marked, like most popular trails in the national park. Basically: keep going up! At an informational sign 500 feet past the trailhead, turn sharp right on the clearly-signed Chapin Pass trail (continuing straight takes you down into the creek drainage).

2. After another 0.5 mile, the trail forks. The lower fork (to the left) is a slightly more gradual climb with a steep push up toward the Mount Chapin summit (12,455 feet), which is easy to reach and worth including. The upper fork (to the right) is a more direct climb (also with that option to zip up Mount Chapin before continuing on). I prefer the righthand trail. Hike one mile to the junction with the Chapin summit trail.

3. After the junction with the trail to the Chapin summit, the Chapin Pass trail continues another 0.5 mile to another junction. To hike Chiquita, take the righthand trail and continue ascending another 0.4 mile to the summit. The views are glorious up here, and it is very difficult for most mountain lovers not to add the summit of Ypsilon, only 1.2 miles away. Just watch the weather (another reason to start very early).

On the search for Chiquita:

I hesitated to include Mount Chiquita in this book at all, but the reference is interesting (if problematic) and the hike is glorious. I first hiked Chiquita from the Chapin Pass Trailhead on Old Fall River Road when I was a teenager. It is a moderate 5-mile round-trip hike to the summit, with the option to zip over to Mount Chapin on the way and to add Ypsilon Mountain out of the sheer joy of being up in the alpine with stunning views in all directions. In a national park that gets more and more crowded each year, it’s still possible to find some true alpine solitude on Chiquita.

But who was Chiquita? The word is Spanish for “little girl,” but the mountain’s name is actually a now obscure reference to the main character of a 1902 novel by Merrill Tileston, Chiquita, the Romance of a Ute Chief’s Daughter. In the book, which is less than masterfully written, a New Englander named Jack travels away from the repressive culture and Christian religion of the East Coast to Colorado, where he finds freedom in the wildness of nature. In his adventures, he sees this freedom reflected most in the Ute religion, particularly in an Uncompahgre Ute chief’s daughter named Chiquita. Jack becomes good friends with Chiquita and pledges to help her receive a nursing education in the East so she can help her people.

In the novel, Tileston dramatizes the historically true violent Meeker Incident (sometimes called the Meeker Massacre) at the White River Ute Indian Agency in western Colorado. Boldly, he describes the subsequent forced removal of Chiquita and her people, compassionately showing how the so-called “Manifest Destiny” was destroying good people’s lives. With the help of Jack and his wife Hazel, Chiquita survives, but she converts to Christianity and adopts white ways in order to earn her nursing degree at a college in the East. Ultimately, the book is a criticism of the forced removal of Native Americans and of the constrictions of Christian “civilization,” with Chiquita a tragic victim of it all. Only once in her adult life, in a visit to Estes Park with Jack and Hazel, does Chiquita feel true happiness again: “her restive spirit broke through the bonds of captivity as soon as the first campfire was lighted. Like a golden-winged chrysalis she broke her civilization fetters and became again the forest-born maiden, Chiquita. No longer did she feel the restraint which society demanded.” On her deathbed, Chiquita rejects Christianity and embraces her Ute religion again.

It was Enos Mills who named Chiquita on the maps, inspired and moved by Tileston’s heroine. Mount Chiquita shows up on a 1919 topographical map of the park. However, why honor Tileston’s romanticized Chiquita and not a real Ute woman, like She-towitch (also known as Susan or Shawsheen), sister to Chief Ouray and sister-in-law to Chipeta (Ouray and Chipeta are both honored with mountain names in southern Colorado) and protector of Arvilla and Josephine Meeker in the Meeker Incident?

It seems likely that Mills, a naturalist, appreciated that scene in Estes Park, when Chiquita longs to discard all of “civilization” and return to the freedom of the West. That moment captures the longing of so many lovers of wilderness in the early 20th century. However, it fails to record the absolute and violent destruction of Ute (and Arapaho and Cheyenne) culture in the area and the removal of those people from their ancestral lands. By memorializing a fictional girl, the mountain’s name makes it too easy to forget the real Ute women who lost their lands and family members and ways of life as Progress roared its way toward them.

And yet -- hike the mountain. On its summit, think about Chipeta and She-towitch, about the women and men and children who journeyed up the Ute Trail each summer, following the elk. Think about the real women who, like Chiquita, had to make impossible choices and sacrifices to survive. Consider the wilderness and all it has witnessed.

Lake Agnes

Lake Agnes, 10,666 feet (MODERATE)

Named for Agnes Zimmerman, pioneer

Getting to the trailhead: Drive up the Poudre Canyon from Fort Collins on Highway 14 to Cameron Pass. About 2.5 miles past the pass, you will see a sign on the left for the Lake Agnes trail. Drive up the dirt road here (there will be a fee, as this is State Forest State Park land). In one mile, you will reach the trailhead. In winter, the dirt road is closed, but you can park just off the highway and snowshoe up. The Never Summer Nordic Hut system rents out lovely little yurts and cabins in this area -- Nokhu Hut on the Lake Agnes Road is my favorite.

|

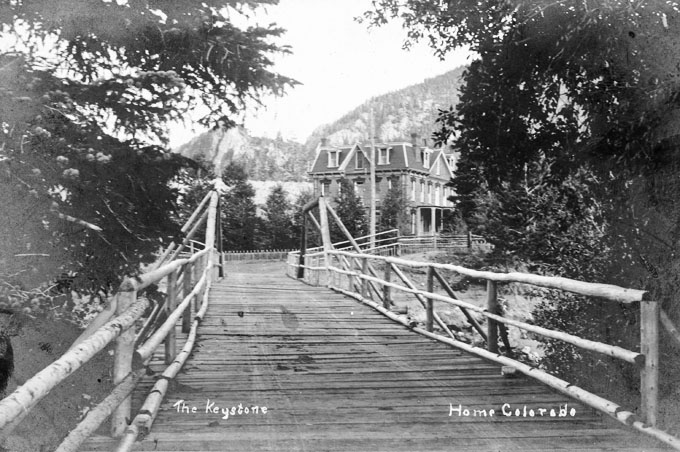

| The historic Keystone Hotel, which Aggie's father built in 1897 |

Roundtrip distance from the trailhead to the top of the hill: 2.3-4.3 miles RT

Elevation gain: 442 feet

Map: [to be included]

How to hike to Lake Agnes:

1. The trail is well-marked. If you choose to walk the dirt road (from Willey Lumber Camp), the first part is a gentle incline. Then, from the Agnes Lake trail, the trail zigzags up to the lake. The views of the Nokhu Crags and the other impressive, jagged peaks (all in the 12,000-foot range) are amazing.

2. If you want to extend your hike, descend to the Michigan Ditch Trail intersection (about halfway up the switchbacks) and hike the 3 miles to the American Lakes trail. Another 2.3 miles will take you up to the American Lakes on the other side of the Nokhu Crags. A different option? Do as I did, and rent the Nokhu Hut on a wintery weekend in November, explore Lake Agnes, wave to a moose, and then return to the woodburning stove and a good book.

On the search for Agnes Zimmerman:

|

| From Barbara Fleming's book Legendary Locals of Fort Collins -- L to R: John Zimmerman, unnamed guest, Eda Zimmerman, John McNabb, Agnes Zimmerman |

Unlike so many of these other names, it was very easy to discover who Agnes of Agnes Lake was: The Colorado Encyclopedia says that “Lake Agnes is named after Agnes Zimmerman, the daughter of John Zimmerman, a homesteader in the area and the proprietor of the Keystone Hotel in Home, Colorado.” That sentence, more or less, is repeated in many different sources. From Findagrave.com, I discovered Agnes was born in December of 1880 and died on May 15, 1954, at age 73. She is buried at the Grandview Cemetery in Fort Collins in the Zimmerman plot.

Of course, I needed to know more. Who was Agnes? What kind of life did she live? Did she love her little gem of a lake at the base of the Nokhu Crags?

I learned from a historic structure assessment of the original Zimmerman Cabin at Lake Agnes that the cabin was built by John in 1882, about a year after he and his wife Marie Schmidt Zimmerman arrived with their four children from Minnesota. Both John and Marie had been born in Switzerland, but had emigrated as young people and had been raising their family in Minnesota. When they decided to venture west to homestead and mine for gold in Colorado, Marie was pregnant with Agnes, and their other three children -- Casper, Ed, and Eda -- were ten, eleven, and thirteen. Agnes was born in December on the covered wagon journey west, when the family wintered in Kansas. Agnes spent her first year bouncing west in the wagon pulled by two oxen; her second year, she toddled around a log cabin beside a lake her father named for her.

At first, John Zimmerman believed he could strike rich with gold mining, but transportation of the ore from his homestead way up the Poudre River proved difficult and expensive. Instead, he turned to tourism: he built and opened the Keystone Hotel at milepost 84.5 of Highway 14. On July 22, 1897, when the hotel opened, the Fort Collins Courier reported the hotel was located in “one of the most picturesque locations imaginable . . . surrounded by some of the wildest and grandest of mountain views in the world.” It was such a success that Zimmerman ran a stage twice a week from Fort Collins -- the twelve-hour trip cost $3. Just a few years later, the Stanley Steamer cars and “mountain wagons” took the place of the stagecoaches.

The hotel was large for the canyon: three stories of brick, with sixteen bedrooms. However, it could not keep up with the tourism industry drawing people elsewhere in Colorado. The blog Fort Collins Images notes that “after the Keystone Resort finally closed despite Agnes Zimmerman’s desperate attempts to keep it going, the land was acquired by the Colorado Department of Game and Fish, now the Colorado Division of Wildlife.” The hotel was torn down in 1946, replaced with the fishery that is still there.

What was the story behind that phrase “desperate attempts to keep it going”? Agnes was 17 when the hotel was opened, and 66 when the hotel was bought and razed to the ground. What happened?

Then I stumbled upon an oral interview with Agnes’ nephew, Robert Casper Zimmerman, conducted in 1977 by a local Fort Collins historian for the Fort Collins Public Library. This kind of source is a history writer’s dream. I quickly discovered that Agnes was “Aggie” to those who knew her, and that she tried hard to keep the Keystone Hotel running after her father’s death in 1919. It was a serious struggle. Zimmerman told his interviewer that, in 1921, when “that road came in up Poudre Canyon,” it “killed the hotel business there” (pg 29). Suddenly, people didn’t need to stop at the Keystone Hotel at Milepost 84.5; they could zoom right by on up to North Park and beyond. Zimmerman said “after the automobile came,” it was harder to find and pay help in the hotel, so “Aggie did all the cooking” (pg 28, transcript). She would have been 41 at the time. She was unmarried. As Zimmerman explained, “I don’t know that Aggie ever had any intentions of ever marrying. If she did, I never heard of it” (pg 30). Her sister Eda did not marry, either.

For Aggie, who had grown into a woman in the beautiful hotel, the struggle to keep the business going must have been heartbreaking. An undated photograph published in Legendary Locals of Fort Collins, Colorado shows Aggie and her sister Eda reclining by the piano, listening with two guests as their father John reads something aloud. With a billiard hall and a barbershop, the hotel at its busiest must have been a haven of a resort. But just as Aggie tried to continue her father’s legacy, the construction of Highway 14 (“by the convicts,” Robert Casper Zimmerman said) ruined it. Her brother Edward died in 1931, and her sister Eda died in 1937. That left Aggie and the eldest, Casper, the only heirs. Zimmerman insisted in the interview that both wanted to sell the hotel to the Colorado Department of Game and Fish (some sources had suggested conflict between his father and Aggie). They just didn’t know, he said, that the plan was to tear down the historic place. “She never would have sold if she’d known they were going to tear it down,” Zimmerman said. “She never in the world would have sold it. She would have lived there and died there. They told her they were going to make a school for game wardens, training game wardens out of that place” (pg 20). Because she believed this, she wouldn’t allow any of the family to remove anything from the grand old hotel -- even the crystal, even the furniture.

Instead, the buyer took everything and sold it at auction, then had the historic hotel razed to the ground in 1946. Aggie, Zimmerman said, “ran it right up until they sold it. If anybody came up there and wanted to stay, she would get them a meal” (pg 30).

When the hotel sold, Zimmerman said, his aunt Aggie -- in her sixties -- traveled to Chicago to study art. “She was a wonderful artist,” he said (pg 30). She painted every wildflower in the canyon -- “she would go out and get the wildflowers in full bloom and bring it in and paint it. She was just unbelievable -- they were so good” (pg 30). Zimmerman had them, he told the historian, some framed and some “in the book that she had.”

I hope, as Aggie lived her last nine years after the hotel’s destruction, that she painted her wildflowers and found some peace. I hope she traveled sometimes -- in cars faster than her father John could have ever imagined as he drove his oxen west to Colorado in 1880 -- up the Poudre Canyon to the trailhead for the little lake named for her. But maybe she just remembered it. After all, though her older sister Eda “wanted to be out fishing and hunting or tracking around the mountains all the time,” “Aggie was more of the domestic type. She wanted to stay around the hotel” (pg 7).

2021 update on Sq**w Mountain renaming

In July of 2017, after some research into Native women connected to this area of Clear Creek County, I submitted a proposal that the USBGN change the name of Clear Creek’s Sq**w Mountain to Mount Mistanta, in honor of Mistanta (also known as Owl Woman). Mistanta lived from 1800-1847 and was the wife of William Bent, who ran Bent's Fort in eastern Colorado. Owl Woman was a respected Southern Cheyenne leader who helped negotiate trade between the many groups who traded at Bent's Fort, and helped maintain good relations between the white people and the Native people. As the eldest daughter of the powerful Cheyenne leader White Thunder, Mistanta worked as a translator and important bridge between the indigenous tribes and the newcomers, in an era before the military-ordered massacres and removals.

I only submitted a name change for the mountain. Next will be the re-naming of the pass, the fire lookout, the road -- and maybe of neighboring Chief Mountain -- but this seemed an important beginning.

I received a confirmation of my proposal. Then, months later in late 2017, the USBGN informed me via email that the Clear Creek County Commissioners Office did not support the name change, as "[we are] proud of our own significant local historic background and heritage.” They also cited the expenses involved in updating maps and signs. I was disappointed, but not surprised. Changing a mountain’s name could not be that easy.

However, in July of 2020, in the midst of the pandemic, I received another email from the BGN that Governor Polis was rejuvenating the Colorado State Names Advisory Board, and they wanted to re-open the proposal. Times had changed. In fall of 2020, Clear Creek Country agreed to the change, I withdrew my proposal so the Arapaho and Cheyenne tribes could submit one with a spelling that is closer to the phonetics: Mestaa’ehehe. A passionate group of Native leaders and activists have been leading webinars to educate people on the harm caused by the word “sq**w” and by honoring people like Evans. The Colorado State Names Advisory Board is working slowly toward the changes.

Hopefully, by the publication of this guidebook, that lovely triangle mountain between Evergreen and Idaho Springs will be officially named Mestaa’ehehe Mountain, and hopefully, from the summit, people will gaze upon Mount Blue Sky (once known as Mount Evans). Hopefully.

Hessie Trailhead

Hessie Trailhead, 9,009 feet (MODERATE)

Named for Hessie Davis, postmistress of the town of Hessie

Getting to the trailhead: From downtown Nederland, drive south on Highway 72 for 0.5 miles, then turn right onto County Road 130. You’ll see a sign for the Eldora Ski Resort at this junction. Drive through the quiet tiny town of Eldora (be sure to obey their speed limit signs!) and park along the gravel road at the trailhead. This is a very popular trailhead; on summer weekends, locals in orange vests will turn cars away after 8 or 9 in the morning. However, there is a great free local shuttle that runs people from Nederland to the trailhead.

Roundtrip distance from the trailhead to the closest lakes: 4 miles RT to Lost Lake; 9.8 miles RT to Jasper Lake; 12.2 miles RT to King Lake; 9.8 miles RT to Diamond Lake

Elevation gain: This depends on how far you would like to venture into the Indian Peaks Wilderness! The elevation gain to Lost Lake is 830 feet. It is 1,942 feet to Jasper Lake.

Map: [to be included]

How to hike from Hessie Trailhead:

1. From your parked car or the shuttle drop-off, walk down the obvious gravel road marked “Hessie Trail.” Be sure to note the remains of the little town of Hessie along the way. In the spring and early summer, much of the first half mile of the gravel road floods, but an alternative trail with boardwalks has been built through the woods.

2. All the trails in this part of Indian Peaks Wilderness are well-marked. The hike to Lost Lake is a quick one, up the old mining road, then a left turn onto a solid bridge over the impressive tumbling Jasper Creek. Lost Lake is a blue gem ringed with lovely mountains -- a perfect place for a picnic (or camping, though note the Wilderness Area regulations). This is officially the end of the Hessie Trail, but it is very difficult to stop at Lost Lake, particularly on a beautiful blue-sky day, when the map shows the Devil’s Thumb trail beckoning upwards. The June day I hiked to Jasper Lake, my dog and I encountered only a few other people -- and snowdrifts to my hips. It was glorious.

On the search for Hessie Davis:

This has been a trail guide for peaks and lakes named for women so far, but I couldn’t help including the Hessie Trail -- and Hessie herself, partly because this trail is a popular entrance to some of Colorado’s most beautiful wilderness, but also because this area preserves the ghostly whispers of a rollicking mining era in the region. Hessie Davis, postmistress of the mining town her husband J.H. Davis named for her, would have known all the gossip and drama that rippled through the area like the telluride gold in the rock.

Early in the morning on a weekday, the Hessie Trail is so quiet, it is difficult to imagine the town of Hessie in 1898, when frantic fortune seekers streamed into Eldora in search of the newly discovered gold ore. Eldora grew to over 1000 people, and the hopeful miners camped in the surrounding area. I’ve always thought the smartest people in these ore boom areas were the ones who sought to profit from the desperate miners (see Clara Brown’s story in the Clara Brown Hill chapter). J.H. Davis was one of those entrepreneurs: he built a lumber mill and founded a town, naming it after his wife. However, the prospectors ultimately discovered very little gold, and the boom fizzled. By 1905, the town of Hessie was deserted. Today, a hiker can see only collapsing structures, sprouting with aspens and monkshood.

Again, though, the official sources do not satisfy my curiosity. Who was Hessie? What happened to her? Where did she and J.H. go after the boom? The interest in the area led to tourism in the small town of Nederland, which thrives today. Did they settle there?

I learned from the Historicorps, which is an organization working to preserve the Hessie Cabin, that Hessie Davis single handedly started a postal facility in the new settlement, and that the miners -- not her husband -- wanted to name the town for her to honor her. Likely, Hessie, like other settlers in the area, grew potatoes, radishes, carrots, and peas, though not much else would grow at 8,600 feet. Unfortunately, her husband’s dream to profit from a lumber mill failed when a forest fire swept through the mountains in 1899.

Then what? According to the 1972 book Colorado Ghost Towns, a Mr. Wilson Davis -- living at the time with his wife in Hessie -- was arrested for the planned murder by dynamite of a fish and game warden in 1914. Was this the son of J.H. and Hessie? I can’t find confirmation. Mr. Davis was released, along with two brothers named Smalley, because there was not enough evidence. The murder remains unsolved.

But back to Hessie. In source after source, I could find nothing beyond the oft-repeated sentence “she quickly made herself indispensable as postmistress” of the new town of Hessie. Then finally, on Ancestry.com, I found a 1900 U.S. Census record: Hessie A. McBurney Davis, born April 8, 1849, in Ireland, lived in Boulder County in 1900, at age 51. I found a marriage record from Virginia (though it shows her marrying a Wilson E. Davis -- did J.H. go by a different name, or is this the wrong record?). I found a death record that showed she died in Los Angeles County on May 29, 1942, at the age of 93.

My favorite record? The one that reveals the most about the mysterious Hessie? She registered to vote in 1920 in California, the moment it became legal for women to do so. I like thinking about 71-year-old Hessie, once the postmistress of a tiny town of thirty people in the Colorado mountains, striding out to vote for the first time in a presidential election in California.

Mount Silverheels

Mount Silverheels, 13,829 ft (DIFFICULT)

Named for Silverheels, the dancehall girl and nurse

|

| Riley on the side of Silverheels, Quandary in the distance |

Getting to the trailhead: This is the first point of disagreement about Silverheels: where to begin? It is possible to hike from the Hoosier Pass parking lot, from Highway 9 up Scott Gulch, or -- if you are lucky enough to own a good 4WD vehicle or have a friend who does -- you can drive up the nine miles on rough jeep trail north from Alma, park by the mine, hop across the creek, and start up. This is how I’ll hike this mountain next time!

Roundtrip distance to the summit from the trailhead:This is the next point of disagreement, as it depends on where you begin. From Hoosier Pass, it will be 8.5 miles round trip; through Scott Gulch, 7.6 miles round trip. From the place you can drive a 4WD vehicle to: it will be barely 4 miles round trip.

Elevation gain: Again, this depends on where you begin. From Hoosier Pass or Scott Gulch, you will gain (and lose!) and gain: 2,949 feet. From the 4WD parking: 1,821 feet.

Map: [to be included]

How to hike to the summit of Mount Silverheels:

There is no trail to the summit of Mount Silverheels. This is part of the reason 13ers are wilder and more challenging than the famed fourteeners in Colorado. It is also the reason I saw no other hikers on my journey to the summit. All of that said, there are, as I noted in “Getting to the Trailhead,” three common approaches. The easiest, by far, is the 4WD option. I’ll describe the one I did, though.

1) From Hoosier Pass, cross the road (to the east) and hike up the very obvious gravel road. This gravel road travels only briefly through forest before it emerges onto tundra and reveals the very daunting view of Mount Silverheels to the southeast (and Hoosier Ridge to the east). The climb up the green slopes of Silverheels looks interminable from here, and many choose to just do Hoosier Ridge, instead.

2) The temptation is to traverse the steep and cushiony tundra and head straight for the saddle in front of Silverheels. However, this is difficult hiking, and requires navigating several talus fields. It is easier hiking (though somewhat more difficult psychology) to continue on the trail toward Hoosier Pass until an obvious false summit at about 12,800, then turn southeast down the alpine ridge toward the saddle. Yes, you lose 800 feet of elevation to reach the 4WD road.

3) As you descend toward the 4WD road, you will likely see a jeep or two parked serenely by a colorful tent, and you will wonder why you did not choose this approach, as you have already hiked a mountain (a twelver, you could say). However, the emerald green dome of Silverheels in the morning is gorgeous, and you will have a far better view than those campers down in the valley.

4) Walk across the 4WD road, then down to the burbling creek (Beaver Creek, near the eponymous iron mine). Then start ascending (only 1,821 feet to go). It is a steep climb, but a spongy one, and the flowers are incredible in the summer.

5) Keep ascending the green slope past a trail that zigs down to a smaller summit, then turn east for the final rocky ridge hike to the summit. Enjoy the views, and be sure to consider the long crowded march of people ascending Quandary to the northwest.

Note: It likely goes without saying, but if you chose the 4WD option, you only need to hike down to your vehicle and then drive to Alma. If you chose my route, you must ascend your unnamed twelver again, then descend to Hoosier Pass.

|

| Forget-me-nots on Silverheels |

On the search for Silverheels:

Silverheels is a famous Colorado legend, so I knew about her even before I began work on this project. The story, told with only slight variations in articles and plays and historical fiction, is that a woman nicknamed Silverheels was a famously beautiful dancer in the mining town of Buckskin Joe, located between today’s towns of Fairplay and Alma. Some sources say she was nicknamed “Silverheels” because of her talent at dancing, but others weave the story that a miner crafted dance shoes for her that were inlaid with silver. Regardless, all sources agree that, when an epidemic of smallpox -- brought to the town by two sheepherders in 1861 -- afflicted the town and the surrounding area, the women and children were evacuated, a plea for nurses from Denver went unheeded, and Silverheels stayed behind to care for the miners and nurse them back to health. Inevitably, she contracted smallpox herself, disappearing into her small cabin on the edge of town. When the outbreak abated, the surviving miners, wishing to thank her, collected money (sources agree that this was the impressive sum of $5,000, which, in 1861, would be the equivalent of $150,000 today) and brought it to her cabin door to give to her. However, she was gone. Some sources say she was so disfigured by the disease that she fled. Others say she died, and that she still haunts the area. All sources agree that the miners returned the money and decided to pay tribute to their angelic savior by naming the beautiful dome of the mountain to the north for her. “Silverheels” started appearing on maps in the mid-1860s.

Of course, I wanted to know more than what the legend offers, so I dug. In the work of one researcher and historical fiction writer, I discovered more elaboration on the well-known legend. On his website, Adam James Jones tells that Silverheels arrived in Buckskin Joe dressed all in black, and that she hid her face behind a heavy veil. When she revealed her face, all were astonished at her beauty. Jones admits, too, that Silverheels was more than just a dancer, as all the unmarried women struggling to make their living in those rough camps had to sell far more than their dancing talent. The commonly told legend tends to omit that fact.

In a compilation of legend versions by Western romance writer Lyn Horner, I discovered that some legends tell that Silverheels arrived in Buckskin Joe wearing a blue and white mask. Others insist that she disappeared after contracting smallpox because she could not bear to let anyone see her ugliness. And finally, some say that she could be glimpsed for years after near the miners’ graves, heavily veiled, weeping.

None of this legend satisfies the historian’s curiosity in me. What was her real name? What about her life drove her to become a dancehall girl and prostitute in a tiny Colorado mining camp? What did she actually think about and love? She’s idealized in all of these legends, an angel, a Florence Nightingale, a selfless martyr. What did she fear? What did she want for her life? Why would she sacrifice everything for miners who viewed her as a luxurious purchase for their bedrooms?

Writers have tried to fill in the answers, as writers do. Breckenridge’s own novelist Helen Rich (see Mount Helen/Belle and Helen Peak) wrote a novel about Silverheels, though the New York publishing house that had published her first two novels (1947, 1950) rejected it. In 1954, Denver University produced the opera Silverheels, and Central City put on a play about Silverheels called . ..And Perhaps Happiness. Several novels have been written in recent years about the legendary Silverheels, too.

However, the legends and fictions have become a thick screen, like we are trying to peer at Silverheels through the silk fabric of a dancegirl’s dress. It is lovely, all that purple color, but we can see only the figure of a woman: now she is dancing; now she is ministering to the sick and dying miners; now she herself is ill. Now she is gone. Who she really was is forever veiled. Maybe all that is certain is that, on many clear mornings in Buckskin Joe, she emerged from her cabin to sip coffee from a tin cup and to admire the great rounded high peak to the north.

Hiking Mount Ida for Ida Ruth

|

| My gram's BH&G profile photo from 1948. The best Ida I knew. |

Some people have assumed that Rocky Mountain National Park's Mount Ida, a 12,889 foot mountain on the western side of the park, was named in allusion to that mountain in Crete. However, my sleuthing -- and my heart, now that I've climbed our Mount Ida -- suggest a different possibility.

When my mother Mary, my sister Katie and I planned our hike up Mount Ida, we compared calendars and found that Saturday, July 28, was the only possibility in the entire summer. Only later did we realize, with astonishment, that that date was the exact five-year anniversary of Gram's death, at age 97 (she would have turned 98 one month later). Of course. We were hiking Mount Ida as part of my quest to hike the mountains and lakes named for women in Colorado, but we were hiking together to honor Gram, the Ida we love and admire and miss dearly. The date was no coincidence.

|

| On the Mount Ida trail (July 28, 2018) |

As we ascended the mountain that morning at 6 am, in silence, our labored breath audible, I wondered about the Ida for whom this mountain had been named. It seems unlikely that the 19th century mountain-namers, who loved to honor themselves and their famous sponsors, would have just named it after a mountain in Crete. Surely, Ida was a woman worth naming a mountain for.

On our hike, the Ida who mattered was Ida Ruth Miller. As the white granite trail climbed upward through the tundra, along the side of an unnamed 12,000-foot mountain toward the right-triangle of Ida, the three of us admired the early sunlight on the Never Summer range, and we identified plants, as Gram would have done: white Yarrow, yellow Arnica, pink Moss Campion, purple Aster, purple Mountain Harebell, blue Jacob's Ladder. Some we didn't know, but we observed so we could identify them later: Dotted Saxifrage, Miners-candle, American bistort. We laughed in delight as the little pikas darted out from their rock caves, as the fat brown marmots squeaked alarms at us. And we climbed.

|

| Mount Ida is the summit to the far right. |

Of the 4.1-4.6 miles (depending on the route one takes through the boulderfield in the last stretch) to the summit of Mount Ida, all but 1.2 miles is above treeline. In the sunshine, beneath a blue sky, that means it is a stunning, expansive, exhilarating hike at the top of the world. It's true that the trail ascends 2100 feet from the trailhead, and that it is a strenuous hike, but it is also glorious, even for those exhausted by the effort. When Mom, Katie and I finally stepped onto the summit at 10:30 am, with a view of the turquoise Azure Lake and the blue Inkwell Lake down the steep cliffs, and the massive flat-topped hulk of Long's Peak rising to the southeast, we congratulated each other on the accomplishment. Mom, nursing a bruised chin from a fall, wanted us to stay away from the steep edges, but she smiled as she ate her sandwich, obviously relieved to have reached the top with us. Above all, we knew, the best way to honor our Ida was in our togetherness. She loved and valued family above all.

|

| On the summit of Mount Ida (me, Mom, and Katie) |

|

| Azure Lake, from the summit of Mount Ida. |

We didn't expect the first thunderstorm to strike only an hour later.

The clouds darkened quickly, blotting out the blue, shadowing the sun, as sheets of rain blurred the Indian Peaks to the south and the Never Summers to the west. Then, a hiker's worst nightmare: an electric white zigzag of lightning that seemed to blaze into the ridge just ahead of us. Katie and I looked at each other with wide eyes. We were still above 12,000 feet, with miles ahead of us. We could glimpse treeline a steep five hundred feet to our left, but it was as dangerous to hurl ourselves down that rocky ravine as to continue on. Between us, Mom kept hiking forward, one foot in front of the other, her head down.

In all my miles of hiking, I have never been so close to lightning strikes as we were that morning. Thunder cracked ahead of us, and freezing rain stung us -- and another lightning bolt zigged to the ground in front of us.

I am not religious, but I hold deep beliefs. I closed my eyes for a moment and thought of Gram, of her deep love for us, of her delight in the natural world, and I imagined a golden bubble around me, my sister, and my mother. And when I opened my eyes, I felt it -- from the east, where Ida Ruth's Bloodroot and Black-Eyed Susan and Oxeye Daisy still bloom, I felt this intense certainty that we three were safe. Another lightning bolt struck ahead of us, and Katie turned to me, panicked, and I said, "We're okay. We're safe," and within minutes, a spherical space cleared around us, a circle of blue sky opened above us, pushing the lightning and the thunder and the rain away from us until we stood in bright sunshine again beneath feathery cirrus clouds.

We hugged each other, hearts hammering, our legs shaky on the tundra trail. And then we applied sunscreen.

It's not that I believe Gram saved us. Gram herself told me, when I asked her in her last year of life, that she simply believed she would nurture the flowers and the plants in her spot beside my grandfather. But there is something besides fatal lightning that vibrates in the world. Great love does. Memory of being greatly loved does. The whole rest of the way down Mount Ida, my mom and my sister and I talked about this. Our legs ached and we wanted iced tea, but every moment had been worth it, if only to remind us how loved we are.

|

| After a high-altitude lightning storm, it's easy to make fun of our fears. . . |

|

| Cairns on the top of Mount Ida. |

And maybe Colorado's Mount Ida wasn't named for Ida Agassiz Higginson at all. Maybe a map-maker loved an Ida who has been lost to history now. Maybe a pioneer named Ida lived there awhile and has now faded into dust.

And maybe Mitike is right: when our family is hiking Mount Ida, we will tell ourselves it is named for the Ida who will always be dearest and most famous to us, Ida Ruth Younkin Miller, lover of wildflowers and names and stories and, above all, the family love that can comfort even in the midst of a high-altitude lightning storm.

|

| Ida Ruth's granddaughter Katie (my sister) on the summit of Mount Ida. |

*

Roundtrip distance to the summit from the trailhead: 9.2-9.6 miles RT, depending on the route

you choose to take through the boulder field

Elevation gain: 2,465 feet

*

Delbert, Jack E. and Brent H. Breithaupt. Tracks, Trails and Thieves: Hayden's 1868 Survey. Geological Society of America, 2016. Book.

Jones, Keith. History of Jelm, Wyoming, Vol. 1. Lulu.com, 19 April 2014, http://www.lulu.com/us/en/shop/keith-jones/history-of-jelm-wyoming-vol-1/paperback/product-21587948.html.

Koster, John. "He tried to solve earth's mysteries and left a few mysteries of his own." History.net, 3 March 2017, http://www.historynet.com/tried-solve-earths-mysteries-left-mysteries-clarence-king.htm.

"Photo Record." Catalog number 2004.024.134. Estespark.pastperfectonline.com, Estes Park Museum, 1940, https://estespark.pastperfectonline.com/photo/63A7BBA5-DA66-47CA-83CF-892962937260.

Sargent, John Singer. "Ida Agassiz Higginson." Drawing, 1917. Harvardartmuseums.org. https://www.harvardartmuseums.org/art/309242.

Sprague, Abner. My Pioneer Life: the Memoirs of Abner E. Sprague. Karen Sue Stopher, 2005. Book.

Brief update on the S____ Mountain renaming!!!

Visit https://mountbluesky.info/ to see where this name change journey has gone! S__ Mountain is now officially named Mount Mestaa’ėhehe (t...

-

This is a screenshot. Click on the link below to go to the actual interactive map. This afternoon, I spent significant time creating ...

-

I love to look at Mount Rosalie. From my sister-in-law's deck in Pine, Colorado, it's a pleasingly rounded summit, a dome blanketed...

-

Although it is not named for a specific woman, I have to discuss Squaw Mountain, which is an 11,773-foot mountain near Idaho Springs, and w...