|

| Mitike walking fast ahead of me on the Flattop Trail -- July 5, 2017. |

My daughter, age 10, stands on the edge of a dusty trail, her feet in their pink New Balance shoes neatly together. As she observes Emerald Lake far below, she chews thoughtfully on a blue Sour Patch Kid, then holds out the yellow box to me. "Want one?"

I shake my head, embarrassed that she has turned to me just as tears have welled up in my eyes.

"Mom? Why are you crying?"

"Because six years ago, I carried you on my back all the way up to Black Lake, and now you're hiking Flattop all by yourself, and I can barely keep up! You're growing up so fast!"

Mitike grins at me and then steps forward to pat my arm. "It's okay, Mom. You're okay." Beneath the brim of her light blue hat ("NORWAY" stitched in flowery letters), her brown eyes are the same brown eyes into which I loved to gaze when she was a sleepy toddler, but every day, she is more awake, more aware, more a person all of her own.

Ever since the days her legs got too long for me to carry her strapped to my back, she has been a reluctant and sometimes petulant hiker. But not today. Today, confidence from her recent week away at camp in Keystone still simmering in her blood, she chooses to climb Flattop Mountain, a 4.4-mile trail that climbs 2,849 feet to 12,335 and views of the Mummy Range, the Never Summer Range, and the Indian Peaks. She strides forward as if she has just discovered her long legs. Once, I have to ask her to stop so I can catch my breath. This shocks her. "Are you okay? Do you need medicine?"

*

As I hike behind Mitike on the trail that zigzags through the alpine, I think about this blog and the challenge I have set for myself to identify, hike, research and map (with my words) all the peaks and lakes named for women in Colorado. I believe in this goal. Already, I have encountered several people -- most of them women -- who light up when I tell them about my project. They want to know who those great women were. They want a guidebook that will tell them how they can hike to those places where those women have been honored by the mapmakers and the U.S. Board on Geographical Names. But puffing to keep up with my suddenly strong and determined daughter, I understand all at once, with something akin to grief's electricity, that too many strong women who passed through or resided in this state never received any recognition at all. And like my daughter, many of those unsung women were women of color.

*

|

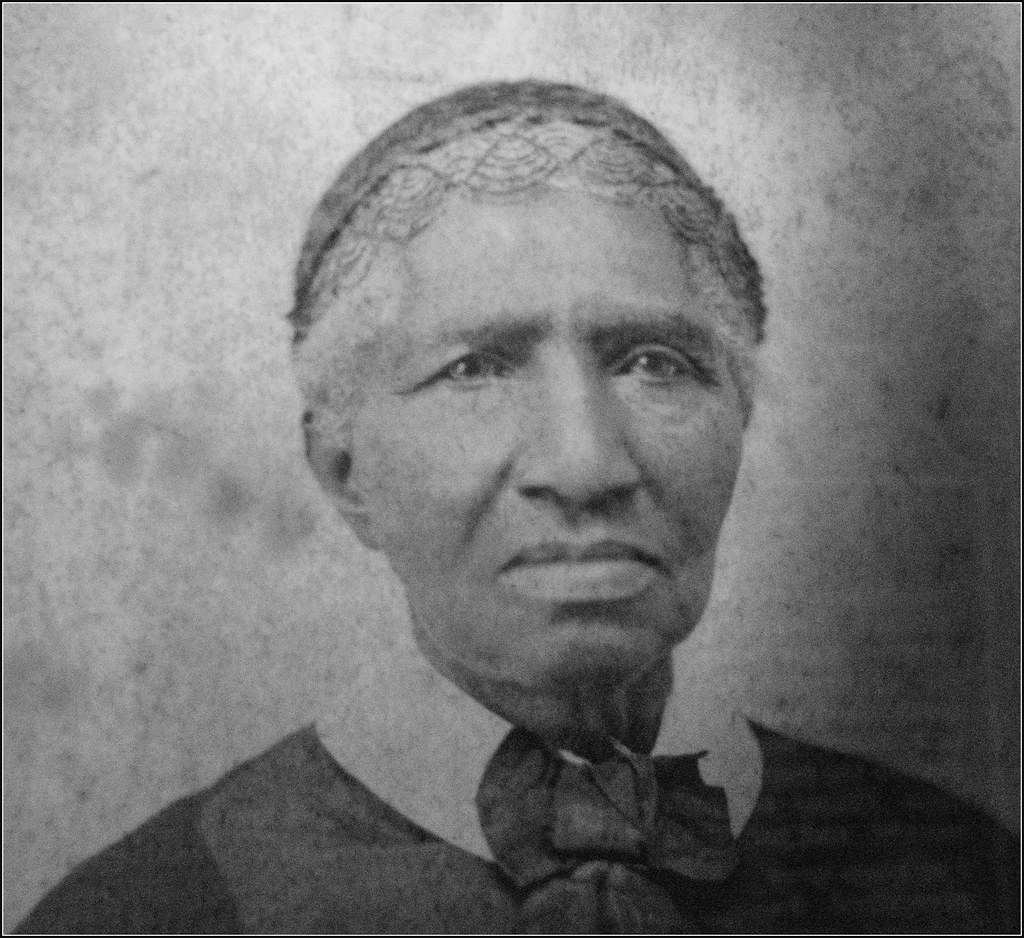

| Clara Brown, for whom no mountain or lake is named, but who has been memorialized in many other ways in Colorado. |

Colorado's most famous African American woman in the 19th century was Miss Clara Brown. Born into slavery in Virginia in 1800, torn from her husband and children by a slave auction in 1835, and freed by a slave master's will at age 56, Brown traveled west to Denver and then to Central City, working as a laundress, cook, and midwife. She managed to save an astounding $10,000 of her earnings (with inflation, that would be about $270,000 today), which enabled her to invest in mining claims and land. She became a respected pillar of the Central City community, but she longed to find the family from which she had been torn in 1835. She attempted to use her considerable resources and influence to locate her husband and children back in Kentucky, but she could only discover that her husband and a daughter had died and that another daughter and a son were lost. Instead, she used her money and her knowledge to help sixteen other former slaves travel west to Colorado, serving as support for them as they got settled in Central City. Then, in 1882, Brown received word that a black woman named Eliza Jane -- the same name as Brown's lost daughter -- was living in Iowa. Brown traveled to meet the woman, and found it was her daughter; they were re-united after forty-seven years. Eliza Jane moved back to Colorado to live with Brown until Brown's death in 1885. At her funeral in Denver, attended by a crowd that included the Colorado governor, James B. Grant, the Denver mayor John L. Routt said Brown was "the kind old friend whose heart always responded to the cry of distress, and who, rising from the humble position of slave to the angelic type of noble woman, won our sympathy and commanded our respect."

Brown has been honored: the Central City Opera dedicated a chair to her in the 1930s, and a stained glass depiction of her life as a pioneer has been displayed in the Colorado state capitol building since 1977. Brown was inducted into the Colorado Women's Hall of Fame in 1989, and Gabriel's Daughter, an opera about Brown's life, was produced in 2003.

Finally, the map-makers honored her, too. In 2012, the manager of Gilpin County convinced the U.S. Board of Geographical Names to change the name of "Negro Hill" in Central City (a hill named for the 1870 lynching of a man named George Smith who had been convicted of the 1868 robbery and murder of William Hamblin in Quartz Valley) to "Aunt Clara Brown Hill" to honor Clara Brown. I'm bothered by the "aunt" part, and wonder why they couldn't have just named it "Clara Brown Hill" (or "Clara Brown Mountain," since the "hill" is 9,089 feet! But there it is. Clara Brown has her name on the maps, and maybe, for a woman as involved in her community as Clara Brown was in Central City, a mountain that watches over the dead in the cemetery and the living in the city is far more fitting than a solitary mountain somewhere above the mining claims.

|

| A topo map showing the 9,089 ft "hill" to the northwest of Central City, which was re-named "Aunt Clara Brown Hill" in 2012. |

*

Other women of color who could have been honored by the map-makers, but were not, include Sarah Breedlove, who arrived in Denver in 1905 as a cook and laundress, starting mixing hair products and marketing them, and soon found herself a millionaire (America's first self-made millionaire woman) who made products that were in high demand. I would (of course) like to hike to a Sarah Lake.

Or Justina Ford, Colorado's first black female doctor, who moved with her husband to Denver in 1902, and who never turned a patient away, even though segregation denied her hospital privileges for many years. The Fords' home now houses the Black American West Museum (open 10-2 on Fridays and Saturdays). I would like to hike the long steady way to a Mount Justina.

I look to southern Colorado, which only became the United States in 1848, when one morning, the ancestors of the people who live in Conejos and Costilla and Dolores and Las Animas counties woke up and lived not in Mexico, but in the U.S. There they have Lake de Nolda, Lake Annella, Dolores Mountain, Mariquita Mountain. But what other Latina women were never honored? I'm excited to dive into research into who Cimarrona might have been (for Cimarrona Peak near Pagosa Springs), but I wonder. Whom did the map makers ignore? Whom did they miss?

Chipeta, the second wife of the Uncompahgre Ute chief Ouray, was honored by the map makers -- Mount Chipeta stands beside Mount Ouray in Chaffee County -- more on that when I successfully hike Mount Chipeta. However, as far as I have researched so far, no other mountains or lakes honor specific Native American women in Colorado.

My objective in this project is to uncover the women who were honored once by the maps, but who have been forgotten, but I see suddenly that my other work is to uncover the histories of women who should have been honored but never were.

*

|

| On the summit of Flattop Mountain -- July 5, 2017 |

As Mitike and I pull ourselves up and over the final snowfield onto the eponymous summit of Flattop, she climbs onto a broad boulder and turns in a slow 360-degree arc. "This," she says, "is beautiful." It is beautiful, as these Rocky Mountain vistas always are, but what I am admiring most is my strong and capable and kind and lovely daughter -- the kind of girl who will change the world -- the kind of girl who should be honored on maps or in stained glass art someday. And yes, I feel like crying again.

Another hiker, a woman, interrupts my admiration to ask Mitike how old she is. When Mitike answers, the woman gawks. "Ten!" A man nearby comments that when he was ten, he would have barely made it a mile up the trail before he would have collapsed into a tantrum. Mitike smiles quietly, glowing. The woman asks respectfully if she can have her photo taken with Mitike at the summit marker sign, and if she can post it on Facebook. Briefly, I wonder if it's Mitike's age or her difference that makes people want to document themselves with her presence, and I know I should wonder about it more, but I nod my ascent, snap the photo, and then glance at Mitike, who is gazing out at the Never Summer range again.

We eat our lunch on a flat rock in view of the top of the world. I observe to Mitike, after we have watched several other hikers crest the summit, that she is definitely the youngest person here today.

"Why does that matter so much to you, Mom?" She has eaten so many bing cherries that her lips are stained red. She looks happy.

I shrug. What I don't say, but we both notice: she is also the only person of color to stand on this summit today. She is the only person of color in the Moraine Park Campground. She was the only person of color at our family reunion a few days before. She was the only person of color at Keystone Science School camp last week. We live in Denver so she is not the only person of color at her school or among her friends, but when we hike out into the mountains, where most places are named for white men (around us loom Long's Peak, Hallet's; below us is Bierstadt Lake and the town of Estes Park), her difference is noticeable.

Does she feel relief when we reach Bear Lake at the end of our hike and see some diversity among the tourists there? An Indian family passes us; an African American family is packing their picnic into a cooler in the parking lot. I do not ask her. Maybe I should. Instead, I keep telling her how proud I am that she hiked to the top of Flattop, that she was the youngest to complete that goal.

Later, we eat ice cream in Estes Park, and I gaze out toward Flattop. My job here, as a woman and as Mitike's mom, is to tell the stories of women who have been forgotten -- and to keep raising a daughter who believes she can become a woman to be remembered.

I say something to this effect to Mitike, and she doesn't respond at first, working to contain the drips of her double scoop of raspberry and strawberry ice cream with her tongue. Then: "Mom, let's enjoy our ice cream. We don't have to think about all that right now." She gestures with one graceful hand toward the mountains. "Be in the moment!"

And of course, she's right.

This is beautiful, Sarah, and made all the more poignant by TK's final comment about living in the moment. Here's to enjoying more hikes and ice cream together!

ReplyDeleteI LOVE THIS. I miss you amazing people. xo

ReplyDeleteYou write so beautifully! Mitike is becoming such a lovely young lady. Such a growth since your last visit to the QC. Love it!!

ReplyDeleteAmazing read, can't wait to read more!!!!

ReplyDelete